Yorgos Lanthimos: Photographs

- Written by Max Olson

- Published:

- In Features

Director Yorgos Lanthimos of Pretty Things tears apart the worlds of his films to put them back together through photography, dissecting the guts of his own artifice.

Dust rises from the rubble of a massive movie set, struck down overnight; the fantastical constructed world of Poor Things now a pile of plywood and grime frozen in medium format. Director Yorgos Lanthimos’ photographic eye, especially when trained on the margins of his film projects, is intent on utilizing the raw material of one medium to create something entirely new in another.

At the opening of his L.A. exhibition “Yorgos Lanthimos: Photos” at Webber 939, Yorgos told art book publisher Michael Mack, “Whatever was gonna happen on set could maybe be transferred into the world [of the photos] instead of reproducing the world of the film.”

The exhibit showcased work from two photo books, i shall sing these songs beautifully, captured in New Orleans during the shoot of Kinds of Kindness, and Dear God, the Parthenon is still broken, shot in Budapest during the production of Poor Things.

These images highlight an artistic process that strips back its artifice by revealing its own guts. The photographs are not an attempt to capture the world of the film, or even his process. Rather than creating uncanny representations of his work, these photographs are a world utterly unto themselves.

As an audience, when watching any film, some subconscious part of us is constantly in conversation with the constructed nature of the world we’re entering. We know that someone built this with their hands, that these are actors reciting lines they practiced. In Yorgos’ worlds, this artifice is almost shouting at us—the stilted language and affect, the larger than life sets—he isn’t trying to trick us into believing what we’re seeing is real. In fact, he is playing with the fact that we know it isn’t. However, the magic trick of his work is in his ability to chase the truth by way of the surreal. In a Yorgos film, the more constructed and off-kilvter his world, the more profound his observations about our own. The absurdity of his brutal universes serve to show us, oftentimes more powerfully than through cinéma vérité, the absurdity and brutality of our own reality.

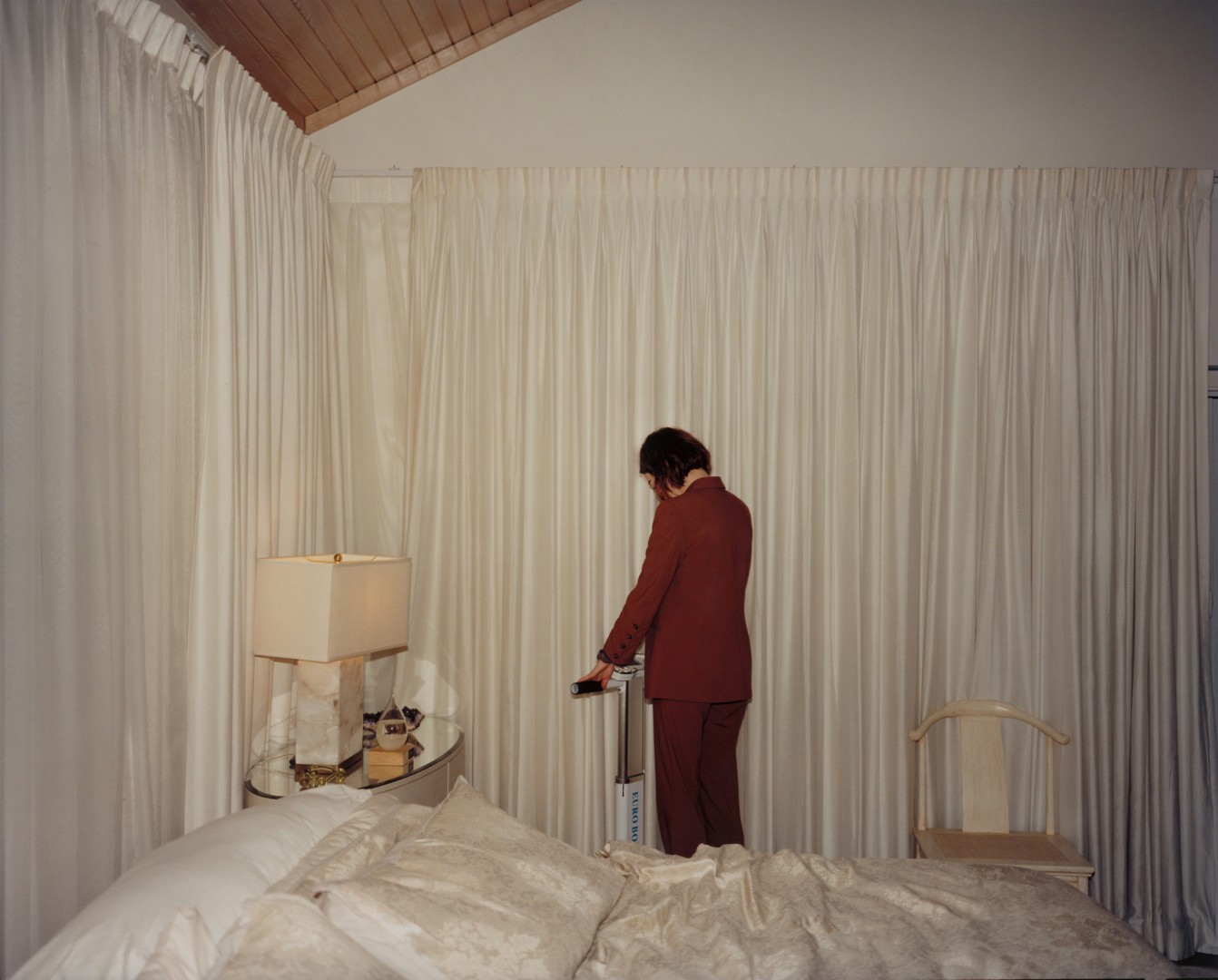

In photographing the highly-constructed worlds he created, Yorgos is disrupting the process by stripping it back to the raw material such that the images feel startlingly alive, like you could reach out, touch them, and hold the viscera of his creative process in your hands. He often zeroes in on textures—the leather of an ancient chair, the fold of a white curtain—inviting us into a tactile reality that stands somewhere far afield of the films he is photographing.

Although Yorgos started taking set photos out of necessity—his early films in Greece didn’t have the budget for a set photographer—on Poor Things this process evolved into something entirely separate because he could then afford to hire an on-set photographer. This allotted him the freedom to take whatever photos he was inspired to take. He worked quickly, stealing shots with actors between setups on his large-format Chamonix and medium-format Plaubel Makina. He snuck behind the sets and viewed his own creation from the outside, taking a step away from the manufactured world of the film and inadvertently creating the otherworldly bardo where these photos live. They often feel like something you shouldn’t be seeing: barren, half-finished sets; Mark Ruffalo in a flowing pink dress; Emma Stone in costume, holding a styrofoam cup and sitting on the hood of a production car.

By taking a step back and viewing his own world from inside and outside simultaneously, he’s playing with what we understand as “real.” But these aren’t slice-of-life photos from a day of shooting, they’re constructions within a construction. He pushed this new creative outlet a step further by taking the reins of the process entirely. After feeling dissatisfied with the images that came back from a Budapest lab, he decided to set up his own makeshift darkroom. He recruited Stone to help him with the processing, which became a meditative ritual to let loose and unwind after the gripping stress of a long day. “You know, we’re filming for twelve hours a day, and then we would go in the evening and process film. After the pace and the excitement, the stress on set.. let’s go home and do this very concentrated meditative thing.”

When it came time to shoot Kinds of Kindness in New Orleans, Yorgos was invested in fusing this meditative practice with a drive to create something more immediate than filmmaking allows. In an interview, Yorgos states “The fact that you take a picture [and] half an hour later you can process it, look at it, print it, hold it. Like it, hate it, whatever…that directness is so satisfying.” The process transformed on Kinds of Kindness, partially because rather than shooting in a studio surrounded by constructed sets, he was shooting on location in a city as vibrant and strange as New Orleans.

The images, shot on a Mamiya 7 and Pentax 6×7, inch even closer to a certain kind of abstract rawness—limbs of a tree spotlit at night, actors often facing away from camera or looking down as if caught in a moment of shame or possessed reverie. This collection also zooms in on the minute details of his surroundings, giving care to people’s hands, shadows, concrete. In some of the images he moves entirely away from familiar casts of characters, walking around the city taking pictures of whatever catches his eye.

Shooting in mostly black and white medium format and using a flash, the aesthetics of i shall sing these songs beautifully are wholly distinct from Kinds of Kindness. The stilted, wildly colorful world of Yorgos’ tryptic is nowhere to be found in the images that appear on the walls of Weber. But it is in the spaces where there is slippage between these two projects, where they meet on a thin line, that Yorgos’ particular lens is all the more present. Even as he works to deconstruct his world, he is still the God of the new one created in its wake. They are undeniably and profoundly his. The images in the book are complemented by haunted, enigmatic poems offering his quintessential mix of absurdity and truth:

He started crying again. She felt nothing. Crying had become his natural state. She urged him to cry more. Harder. Hold nothing back. Later that night he died.

These two collections are not the end of Yorgos’ foray into photography as his primary medium but they may be the end of this work using his film sets as a vehicle—at least for the moment. After releasing his upcoming film Bugonia, his third in three years, he is looking to take a break from filmmaking. When asked about how he keeps his work fresh, he responded, “You caught me at a point where I’m trying to rediscover fun…I need to get back to you on that.” But having recently moved back to Athens after ten years abroad, he is finding himself re-inspired by his home. As he dives further into this new medium, we can be sure the images will remain a reflection of his peculiar world. “I’ve been taking photographs outside of Athens…I see all these absurd things in front of me all the time…I guess I’m quite attracted to that.”

On View at 939 S Santa Fe Ave, Los Angeles, 90021. Wednesday - Saturday, 11am - 6pm.

"I shall sing these songs beautifully" (2024) is published by MACK.

"Dear God, the Parthenon is Still Broken" (2024) is published by Void.

Share