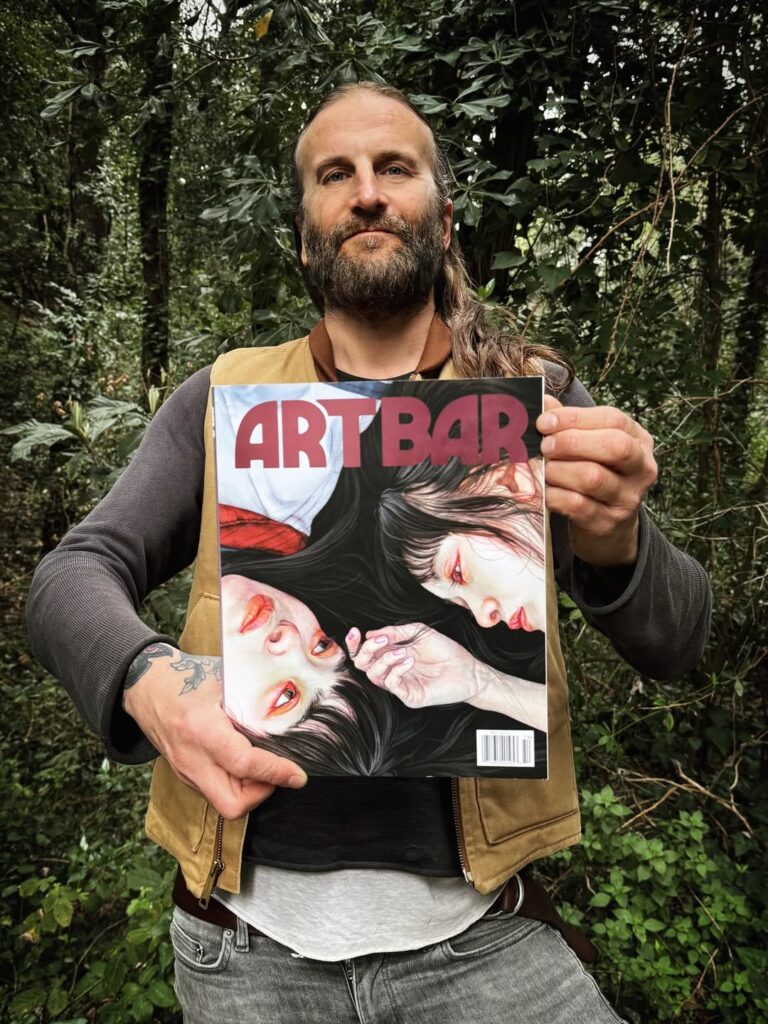

Jerry Hsu: A Vague Hope

- Interview by Christopher Blauvelt

- Published:

- In Features

To be able to print conversations between visionary artists like the one you’re about to read, was a defining motive while conceiving Art Bar. Our dear friend and filmmaker Christopher Blauvelt sits down with revered skateboarder and photographer Jerry Hsu. Their dialogue conjures up a bouquet of fresh film canisters, spilled coffee in a used book store, and hot wet asphalt.

BLAUVELT: Did you pick up the camera or a skateboard first, and how old were you?

JERRY: Right before I turned 12. You know, you’re at that Standby Me age, where you’re really searching (or I was, anyway), for something, like “Who am I? What do I want to do?” Maybe that’s a little bit early for a kid to be thinking, “Who am I?” [laughs]. It was a time in my life when I liked video games. I liked riding my bike. I liked just going to my friend’s house and watching movies. It was really like slumber parties, just normal kid stuff. But there was something else that I wanted.

I think I just kind of wanted… maybe I wanted to fall in love with something? Maybe that’s what I was looking for. When I discovered skateboarding, that’s kind of what happened. It just hit me like a ton of bricks, and I didn’t even realize it at the time. It’s all I was thinking about. I’m at school all day just thinking, “Oh, I can’t wait to go home and skate, and I can’t wait to skate with my friends.” Whatever I could sort of discern about the culture as a little kid was also really interesting to me. I think a lot of kids, when they first get into punk or hardcore, are like, “What is this? I need to find out everything about it.”

There was a subculture, at the time, this was in 1992. Skateboarding wasn’t a very cool thing to do [both laugh]. And that also interested me because before that, I was so obsessed with fitting in, you know, I kind of was just doing whatever I thought my friends wanted to do or whatever I thought other kids wanted to do. I really did not want to stand out. But for some reason, when I started skateboarding, nobody thought it was cool. And for some reason I liked that. I had made some kind of switch where I was just like, “Ooh, I kind of want to do something that’s a little bit weird, and I really want to dive into this weird underground world.”

BLAUVELT: Yeah, I could see comfort coming from a rebellion too, you know? You have your thing.

JERRY: I think the rebellion aspect was really kicking in at the time. ‘Cause I remember I was acting out a lot. I was stealing, getting caught stealing. I was, you know, smoking weed at school, I got expelled from this school. My parents were just like, “What is going on with this kid?” And skateboarding just kind of happened to overlap with that. So they really blamed it. But it really was just a time in my life where I was sort of acting out against expectations of me from family and what I perceived as society at the time.

BLAUVELT: Yeah. It’s funny. I think it’s probably true for a lot of people. Your body’s hormones are growing and you don’t know what to do. It’s like watching a cat that has this energy and it doesn’t know what to do with it.

JERRY: I think that’s totally true. I also think friends you meet at that age make a really, really big difference. And it will echo throughout your whole life. And I did meet those people, where I started to experience other kids’ lives that were going through the same thing as me. We just lived off of each other’s creativity, angst, that sort of desire to explore. It’s out there.

BLAUVELT: Yeah. And were you also shooting at that time?

JERRY: No, not really. In the very, very beginning, I had always loved art. I’d always loved drawing and painting. And before I started skating, I was really into comic books. So I was always trying to draw comic book type stuff. I think when I started skateboarding, and once I discovered videos and magazines, was when I started to be like, “Oh, it’s sort of a natural skater thing to want to record yourself and your friends.” I would take my mom’s video camera and we would just film each other with it. I would take the family camera and shoot photos of us trying to skate — you know, like launch ramps and stuff. But it really didn’t kick in until I was 16. Then I started to discover photography as an art form.

I’m from the suburbs in San Jose, so there weren’t really any cool bookstores that I knew of or had access to. But we would go to Barnes and Noble and they had the art book section. And it’s funny because they actually had pretty cool stuff at the time. You could find Larry Clark books, Nan Goldin books, Jim Goldberg, Bruce Davidson and other artists like that… I used to look at those a lot. And also at the same time I got sponsored as a skater at 15, 16. And that’s when I started meeting professional photographers. Hanging out with them was cool because they could answer any question I had about how a camera worked and they could tell me what cameras to get. I also noticed people like Ed Templeton who was a pro skater and he made photos, and I liked his photos. I think his influences overlapped with mine, even though he was older and much wiser. The sort of Nan Goldin, Larry Clark, Jim Goldberg pipeline. I could see it in his work. That was influential too because it showed me to shoot the stuff around you — shoot your friends, your traveling around. I think it helped me develop my taste.

I think photography, the type that I do, is mostly about coping with failure. It’s mostly about coming home with nothing. And that’s kind of tough. But over time, if you just put yourself out there enough, it’ll happen.

BLAUVELT: Yeah, it’s really interesting. I think my experience with a camera began with my father being a camera assistant. There were always cameras around. I wasn’t a very good skateboarder. I wasn’t the coolest punker either, so it was something I could fall back on, because people wanted you to shoot from your experience, creating more of a human connection with your camera with people that maybe weren’t skaters or punkers. Did you find that to be true with your life?

JERRY: I find that to be true to this day. Kind of in the same way that skateboarding was able to bring me out, because I’m very introverted. Being a skater really helped me experience new people. And I’m very shy, so you know, you just get in the car with your friends and then you run into other crews and you become friends. And it’s this whole hidden community. And with photography, it was a little bit different because the type of photography I was drawn to forced me to talk to and confront strangers or situations that without a camera I would never be able to penetrate. I think in that way, the camera really is a tool that helps me fight my introvertedness and connect with people and my environment, because otherwise it’s tough. And to this day, I’ll wake up and I’ll say to myself, “Okay, today I’m gonna go, I’m just gonna go all day. I’m gonna try and shoot.” And literally nothing can happen. But the camera helps persuade me to just show up. And it does that in a lot of different ways.

BLAUVELT: Yeah, it’s cool to hear your perspective on that. Life, and photography, and appreciating other people’s art; all these photographers you’re mentioning are the same in my life. But after seeing your work, I don’t think I have the ability to do that. I always shy away from going for the moment, more times than not. And for you to say that you’re an introvert, it’s kind of crazy to hear actually because I feel like I’m maybe more of an extrovert in a way socially. But I don’t wanna impose myself when it comes to shooting.

JERRY: Yeah, me neither. It’s funny because it’s a real contradiction with me, because I sort of go for it a lot. But at the same time, I also feel like it’s not enough. A lot of creative people have to struggle with this. I’m never satisfied. I think people very generously compliment me about the volume of stuff that I’ll put out. But deep down I’m like, “I could go so much harder if only I was so much more focused.” I try not to think about that too much, but it’s nice motivation also. Also with photography… if you miss something, if you let something go, or if you were too scared, you just weren’t brave enough to go up to somebody… oh, it just haunts you [laughs].

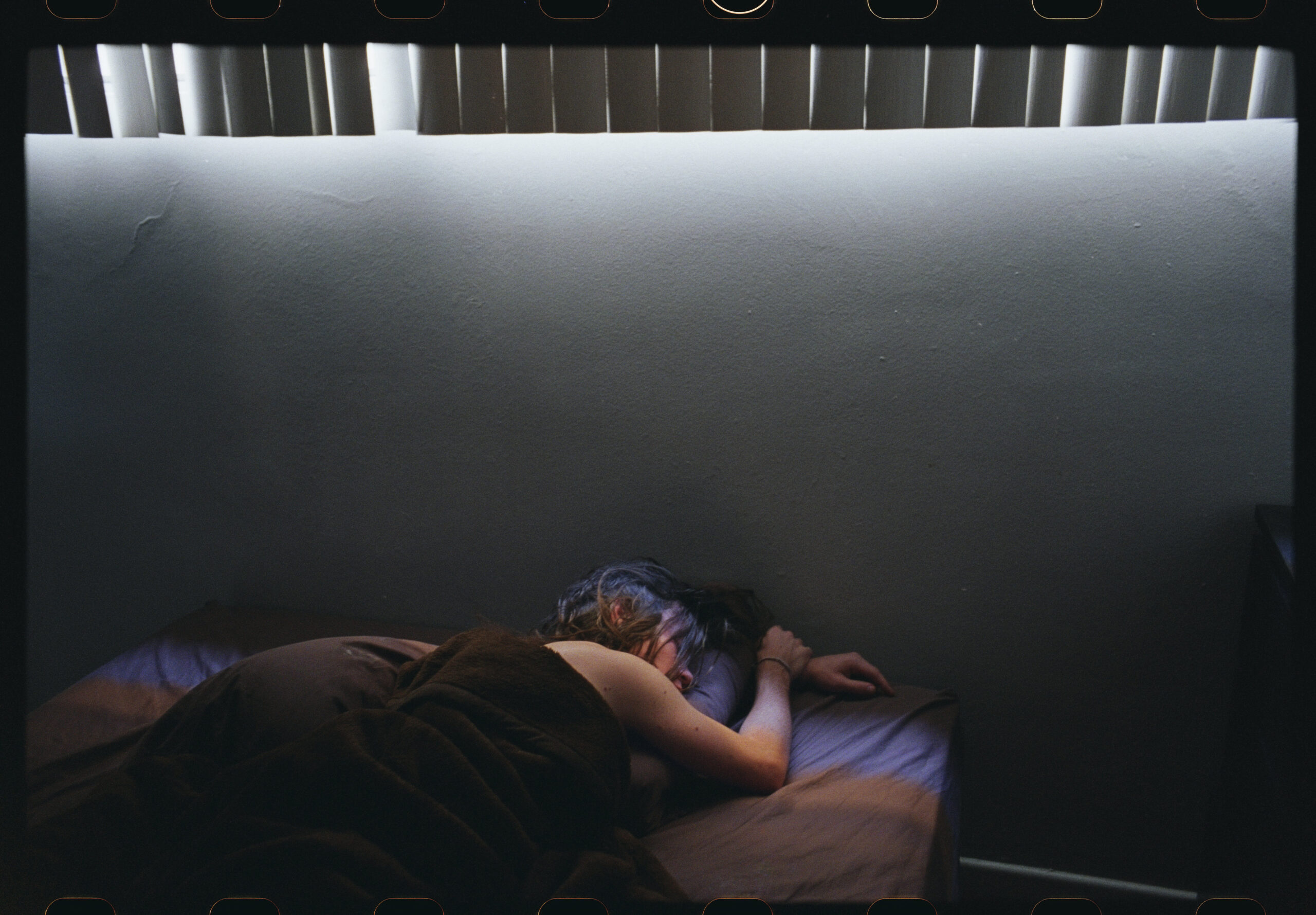

It haunts the hell outta me. Lately, most of my photography hasn’t involved people. But when I do go after something with people in it, it’s not just overcoming fear. It can be hard to have a creative practice that’s not rewarding very often; but when it is, it hits. I have a lot of friends who are writers and I relate to them a lot, because you just have to write every day and not think about what you’re doing. You just have to sit down and do it. It’s work. And I really relate to that in the world of photography, because out there it’s almost purely instinct. I try to not think about what I’m doing at all, just do it. And then when you get your photos back, you can find the stuff that you were looking for. You also don’t really know what you’re looking for yet. I like to call it just a vague hope. You have to have a vague hope every day. And because taking the photos and editing the photos together into something that you’re going to present takes two totally different parts of the brain. I try not to think about anything when I’m out there — just shoot all the time.

It’s like skateboarding. It’s not thinking about coming up with an idea, it’s about thinking and executing. It takes focus and experience. But I think that landing a trick, especially if it’s hard or dangerous or scary, is mostly about letting go and just letting your spiritual muscle memory kick in — and then you’ll do it. It’s often a real surprise. This happens to me a lot in my life where I’m trying so hard for hours and hours and hours and days and days, and the one time where I truly let go of everything, I land it. I think that’s a metaphor for getting photos of what you want. You just have to have this faith when you go out there. I try to remind myself of this all the time.’Cause looking for Something is hard. You probably won’t find it. But if you look for Anything, something will be in there.

It’s a way to just get myself out of the house. It’s my way to keep going. I want to give up all the time when I’m out there. It’ll get to be three, four or five o’clock and I’m like, “Nothing has happened today.” But the times that I’ll turn one more corner and something happens and then I get the photo back, I’m like, “Oh, I’m so thankful that I just kept going. That my curiosity let me go a little bit further.” I think photography, the type that I do, is mostly about coping with failure. It’s mostly about coming home with nothing. And that’s kind of tough. But over time, if you just put yourself out there enough, it’ll happen.

I’m just so grateful that I have something that helps me extract something from this world which sometimes feels like I don’t belong in. But this makes me feel like I belong in it.

BLAUVELT: By nature you are sticking with it. So there’s an optimism built into the discipline that you have just to stick it out.

JERRY: It’s that vague hope that you’ll get something you want and that will fit into the sort of the work that you want to make. So I think it’s also about faith. You have no proof, but you’re just going to believe that if you go out there, you might find it. And it is out there. I’m constantly impressed by the amount of weird stuff that’s out there. And it doesn’t matter where you are, man. I think if you just dig deep enough, there’s stuff everywhere all the time.

BLAUVELT: Are you an ambulance chaser? Do you have a police scanner? Are you a pyromaniac? How was it plausible to stumble on all these incredible scenes? Rabbit’s Foot?

JERRY: [Laughs] So yeah, I get asked this a lot. LA is just a dense metropolis in its own way. It’s not like New York City, it’s much more sprawling. I would come across a lot of destruction, and of course I’m gonna stop and capture it a little bit. And then, I was just like, “Oh, this stuff’s kind of cool. I don’t know what I’m gonna do with it. But it’s interesting to me.” It’s a pattern. And I think photographers, they’re just obsessed with patterns. But… I ended up getting that app Citizen.

Citizen is basically a user generated app that I think is connected to 911. Basically if you have the app and you see something, you can report it to the app and it will tell the people that are nearby. It’s kind of like a police scanner, but it’s user generated. And so I’ll get these alerts and, to be honest, a lot of them are bogus. A lot of them, they don’t exist. I’ll go to a thing that is happening at this intersection and I’m nearby. I’ll go check it out, and nothing’s there. So it’s pretty unreliable. But I do use it to find a lot of real stuff too. I come across a lot of stuff naturally, but I think no person could really stumble upon that many things that naturally. There is a tool.

BLAUVELT: But also you’re disciplined for just being out. And this is a moving city with cars and a bunch of people and bikes. So just being out there, you’re functioning in your way where you’re like, “I’m gonna photograph what I’m seeing.”

JERRY: That’s why I have to be alone a lot. It’s a nightmare to be with me because I’m pulling over, I’m turning around, I’ll wait somewhere for twenty minutes, thirty minutes, forty-five minutes. I like going out at night just by myself. Then I can just work at my own pace, because there is just so much waiting. You kind of gotta go the extra, you know? You gotta do the extra thing to get some of this stuff.

BLAUVELT: Worst Uber driver ever. Do you know Tobin?

JERRY: Yeah. I love Tobin. Tobin’s actually a very early influence too.

BLAUVELT: I was gonna ask that, ’cause you mentioned Larry Clark.

JERRY: I remember I was told, he took a class with him.

BLAUVELT: And he introduced Harmony [Korine].

JERRY: Yeah, that’s right. I think Tobin and Ed were a very early, early influence. And the whole shoot photos of your friends thing, you know. And his access to the people around him, especially in the early nineties, I was just like, Wow. As a skateboarder, being able to see John Cardiel or Tobin or Corey Chrysler or all those other crazy guys that he was around blew me away.

BLAUVELT: Andy Roy.

JERRY: Yeah. Andy Roy. And the photos, he’s just so good. Tobin’s great. I admire him a lot.

BLAUVELT: I have friends who are the most incredible creative directors and cinematographers and everything else. Like Gus Van Zant, he was a hero of mine when I was a kid, and now he is just a good friend. I feel like in the same way you were mentioning how people that are sort of searching, or they see the world in a different way. Because you get so much back from it. Do you think there’s a correlation between someone like Gus, who is honestly just like walking around with a child. ’cause he’s like, “Oh, Chris, like, look at the butterflies, or the wind blowing.” He’s just so aware of the beauty that the world is always giving.

JERRY: (to himself) How to answer that?

The world and the reality that you live in can be difficult to cope with sometimes. But if you can extract some kind of beauty out of it, whatever that is, it’s nurturing. It’s easy to grow up and lose that childlike curiosity about the potential of the world. And that can be a kind of a dark place to live in. I’m just so grateful that I have something that helps me extract something from this world which sometimes feels like I don’t belong in. But this makes me feel like I belong in it. I love seeing and capturing these things. It makes me appreciate being here. And I think that’s something that I’m so grateful for, ’cause I don’t know how I would do that without this, you know?

Share

You might also like ...

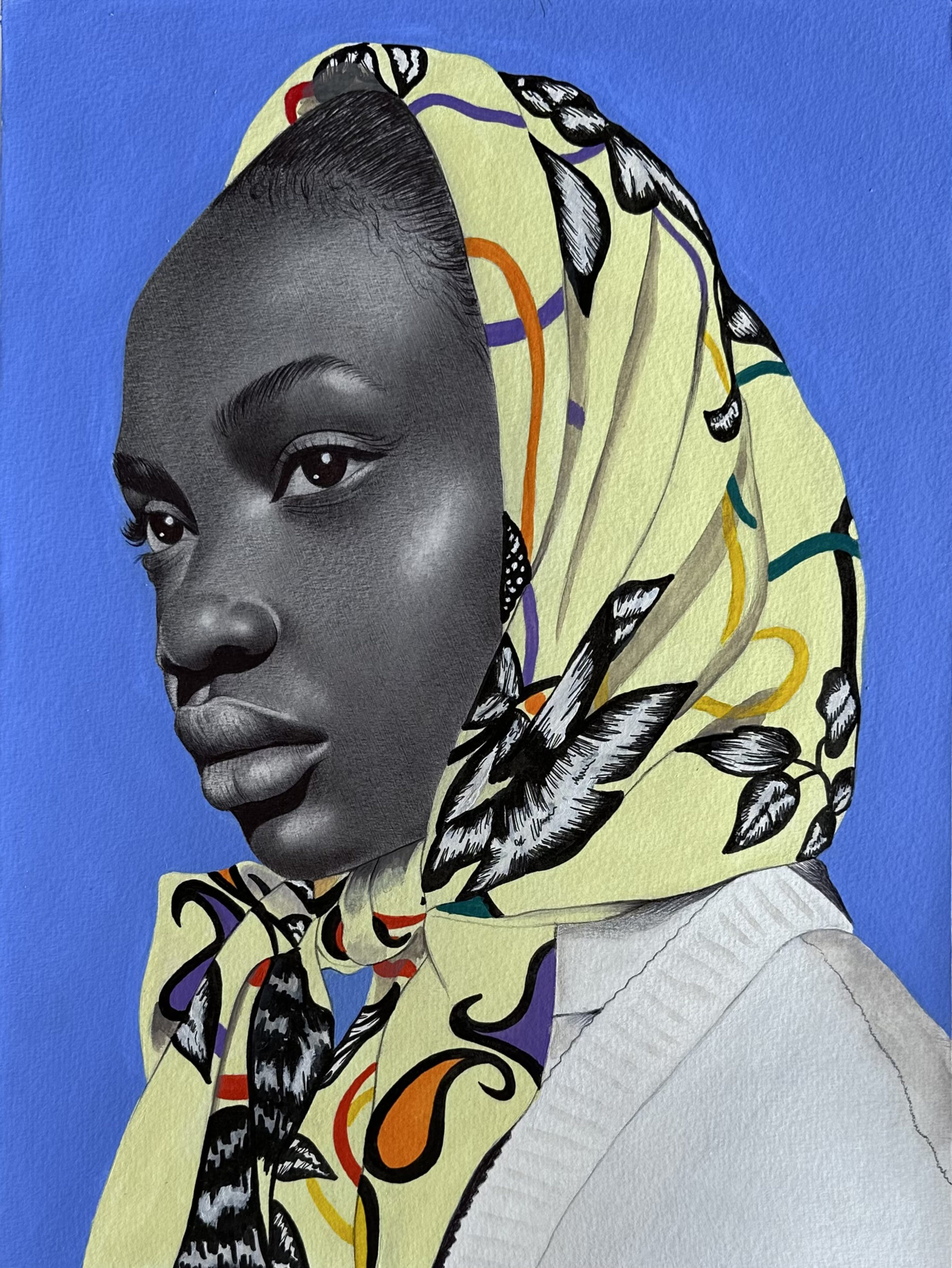

Zara Kand: Dream World

Zara Kand alchemizes grief into portraits of dream-like beauty infused with Jungian symbolism.

Tommy Mitchell: If You Dream, Life Will Pinch You

Tommy Mitchell has mastered the humble ballpoint pen over the past few decades, while continuing to push his work into new frontiers.

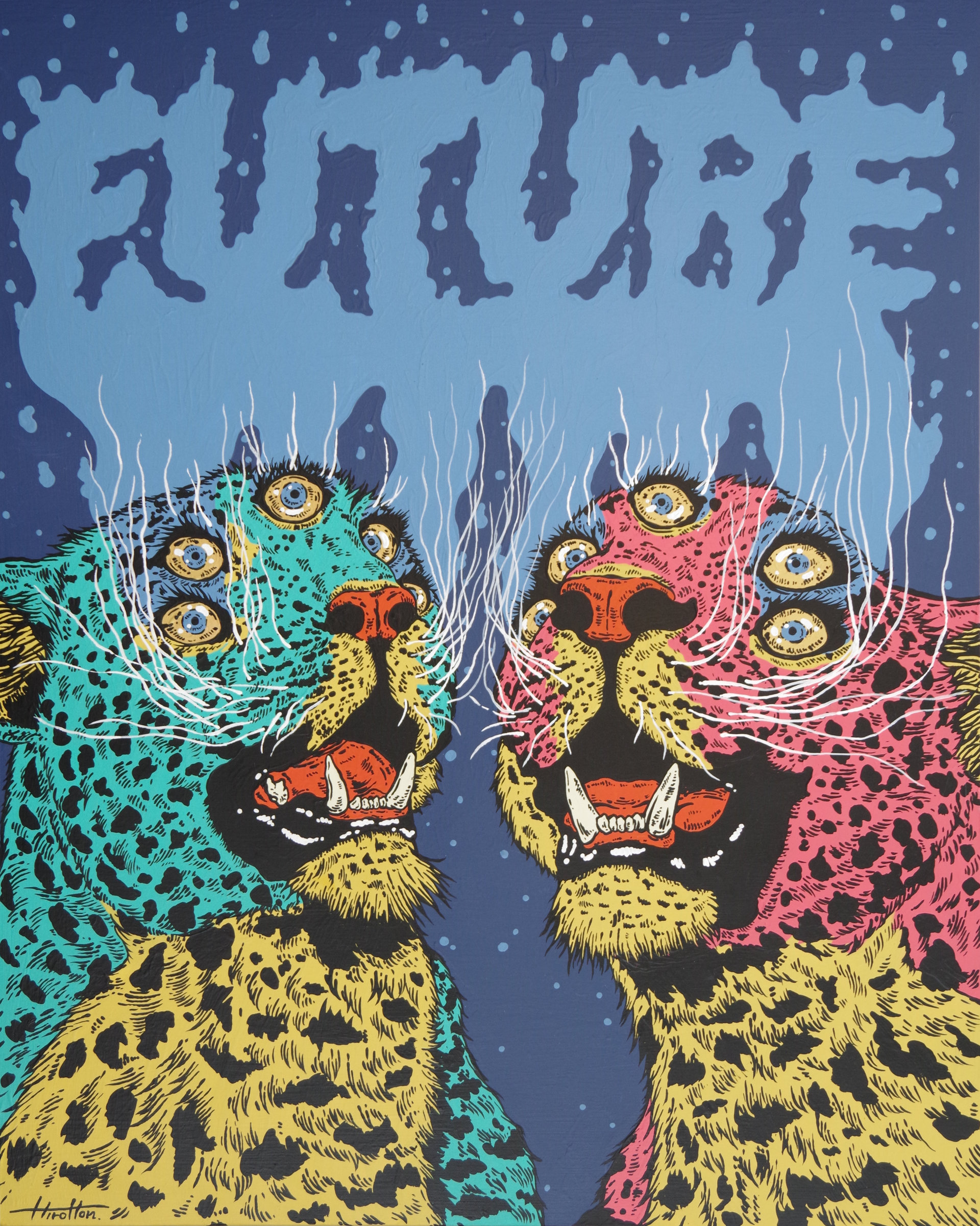

Hirotton: A Future in the Past

Hirotton cut his teeth as an artist in the streets of Osaka and went on to distill his work in London, like so much fine gin. While his punk rock roots still endure in his paintings and drawings, they also reveal a magical world that’s all his own.

Various Artists: Shadow Work

Healing the Jungian shadow-self through dark art. Curated by Diana M. Ahuixa.