Andy Woll: Wild at Heart

- Written by Max Olson

- Published:

- In Features

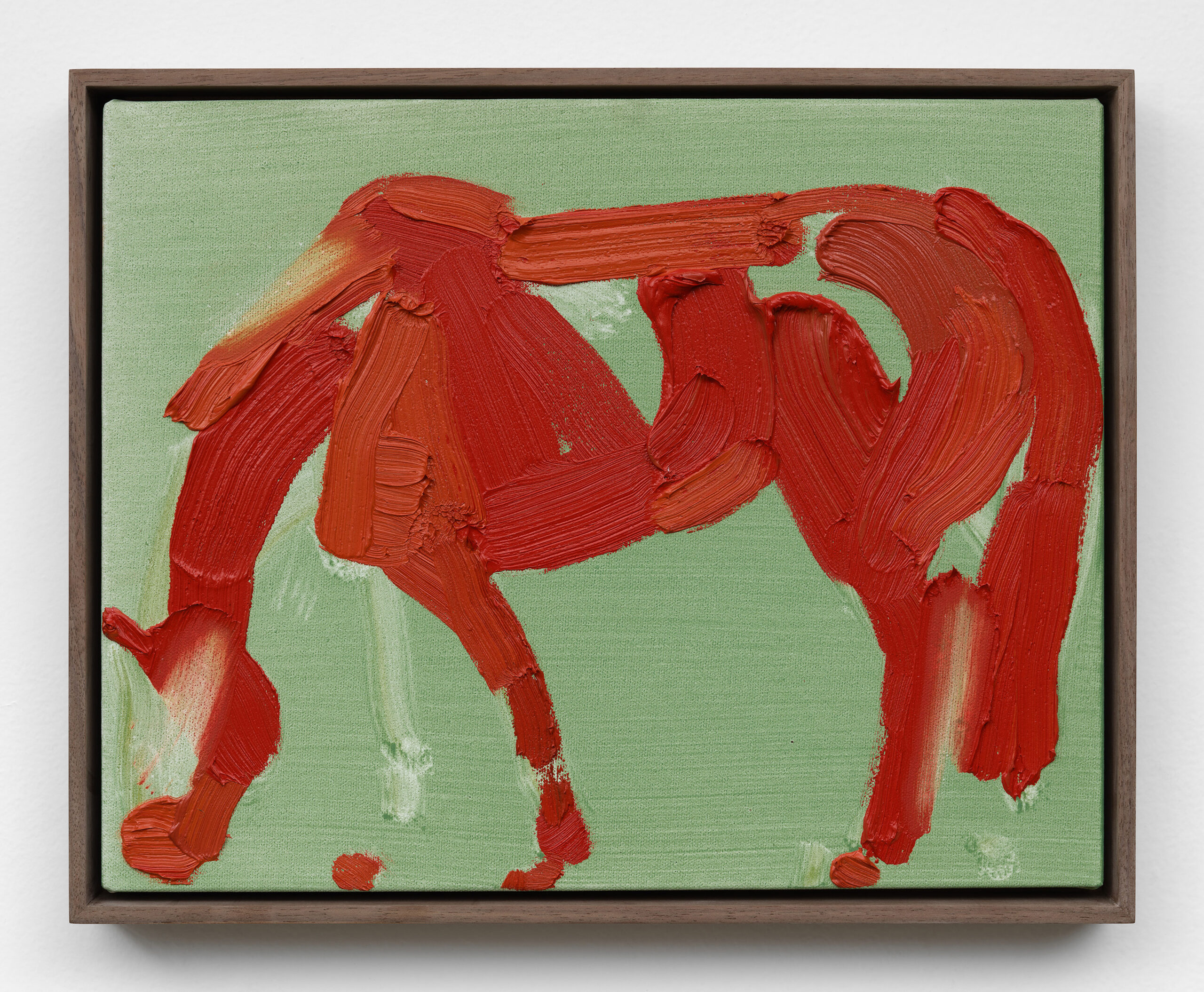

Andy Woll’s artistic path began not in the classroom, but as a restless spirit sketching birds in the back of the car. Having weathered deep loss, this untamed artist approaches both life and creativity with raw, unbridled honesty. Much like the powerful, “misbehaving” horses he now paints and rides with a ritualistic devotion, Woll finds his stride in the studio, constantly evaluating, layering, and sometimes even destroying, all in a relentless pursuit of connection that mirrors his own wild soul.

Art Bar: Where were your first seeds as an artist planted?

Hard to say. But my parents, my dad especially, used “drawing in a sketchbook” as a parenting strategy. He’d just give me a blank sketchbook, and I would copy The Illustrated Birds of North America; I would go through the book and copy all the birds I thought were cool onto my sketchbook. That’s the earliest I remember. We used to take a lot of road trips, and so I’d sit in the back of the car drawing, just trying to kill time.

How’d you eventually find your way into art school?

I dropped out of high school – I was working as an apprentice or something at a tattoo shop, but I needed to make more money, so I went to work at Hollywood Video. I hated that. So, I decided I would try and get into art school somewhere. I didn’t know if I wanted to be an artist necessarily, but I knew I was good at drawing. So I got my GED, and at the same time, I applied to one art school: Otis. They let me in, never checked for my GED, whether I had it or not – it didn’t seem to be an issue.

In what ways did art school change your perspective on school?

I would say that art school was kind of the first time I went to school and I felt comfortable, or good at something. I dropped out of high school, and elementary through middle – it was all just a series of failures and anxiety. I really didn’t like it. I was lucky at Otis to have a good group of teachers, especially once I got into the studio art program. Those friends and peers are still the most important people in my life.

After art school, what was the move?

I graduated from Otis in 2007, and moved to Berlin later that year. I lived there with my girlfriend, Holly, from 2007 to 2009.

Moving from Southern California to a foreign country with a lover sounds like every post-art school grad’s dream – how did Berlin influence you, creatively?

We were making art. We were living in this really cheap apartment, making art, painting murals and stuff. People would open a bar and just have us paint the whole outside of the bar. Berlin is covered in graffiti. We weren’t graffiti artists, but they would just have us do murals. We were working in the apartment, and then eventually, most of what we were doing in Berlin was not productive art making. Just mostly partying, and yeah. Getting into trouble.

What was life like after Berlin?

Holly died in Berlin in 2009. I was in the States. I was actually arrested in Nebraska at the same time she overdosed, in our apartment in Berlin. Heh. That’s not funny. But in that way, comedy and tragedy are like the opposite sides of a coin. I was arrested in Nebraska, so they had taken my passport, and I couldn’t go back to her in Berlin.

I have one question about mortality, I didn’t know if you wanted to talk about it…

Yeah, mortality, the broad concept of mortality…

I think that a person’s artwork is not like completely a strategic decision consciously made, you know? So, I’ve picked up from all of the important experiences and people in my life. Little pieces have been left with me and that definitely comes out in my “art” in terms of mortality.

The biggest thing for me was that when she died, I thought to myself, now I want to die. And then I kind of went on that trip for a few years, and realized that I didn’t want to die. And then the realization that my own suicidal ideation was a failure, meant that I had to take life seriously, and I had to figure out what I was gonna do with my time.

I was just on a death spiral. Making stuff now is a product of me deciding to be alive

What did you figure out?

It was probably the thing that made it so that I had to get sober. ‘Cause I just couldn’t live the way I was living for very long, and that wasn’t a one-moment realization. It took a long time. I wasn’t really making stuff when I wasn’t sober, I was just on a death spiral. Making stuff now is a product of me deciding to be alive.

Extremely profound words. What brought you back, from that moment of inexplicable darkness, to the decision of “wanting” to be “alive”?

As an adult, drugs and alcohol helped me fill the void that I was filling with sketching when I was a kid. I’m able to use that void more productively now. I fill the void with work and busyness. It’s just something about my psyche. I can’t stop planning and working.

I don’t know the full evolution of your work, but I know that it wasn’t always horses.

My work is the preoccupations that I have. I take those seriously. The first thing that people really cared about were the mountain paintings of Mount Wilson. I started making these paintings, sort of like a game of telephone. The last painting that I made would influence the next painting that I made. And then that painting would influence the next one. I would just let little things come in, like the Velazquez paintings, the old Spanish Golden Age stuff. I would put that into the mountain. And then working with the horses was another preoccupation. So I started painting them. That’s become a long series. I don’t know what makes certain preoccupations more important than other ones. Like, I think about my dogs a lot, but I don’t paint my dogs.

Do you see something about yourself in the horses that you ride and work with?

I think that when you sit on a horse, you have to want to be riding that horse. You have to, in one sense or another, love the horse. You might not love the way it’s acting or what it’s doing, how it’s behaving. But you have to be able to think like, I want to be on this horse. I want to work with this horse. And so, I do think that my own wildness lets me relate to those kinds of horses.

And when you say, “those kinds of horses,” what do you mean?

People don’t want me to ride their nice-finished, well-behaved horses. The type of horse that people offer me to ride is one that’s a little bit misbehaving, a little bit wild. These are adult horses that are difficult to ride. Bucking, or either don’t want to go, or wanna go too fast.

I relate to them. Having been a bit of a problem person and having come out of it, knowing that that’s possible. I can see that I’m the good horse that’s underneath that bad behavior. It’s like the horse that I have is, in some way, sort of just like me. You know?

What’s the reality behind your “artistic process”?

I sort of had these experiences with paintings throughout my life where they made my life better, in hard-to-describe ways. Just seeing them or having them around. A painting has this ability to be this weird little handmade thing with a strong influence on the room. I became really attached to that kind of an object.

What mediums do you use in your technical process?

So they’re pretty much all oil paintings, oil on linen. I’m really good at gessoing, which is how you prepare the surface. I’m quite proud of my gesso technique. I paint in a lot of layers. I’m a brush painter. I work with these crude hog bristle brushes, and I’m not very good at cleaning them. I try to keep stuff more or less clean. The paintings themselves end up being more about the painted surface than about the content. I’m always just working and evaluating and then deciding whether or not to destroy the thing.

I’ve seen you just sit in your studio and stare at the paintings sometimes.

Right. If I was to be painting that whole time, for one thing I’d be broke, and for another, I would have a ton of crappy art. I’ve learned to pace myself and not paint when I come in here. I’ll sit and look, or take a nap, or just be in the room with the stuff. I try to get a feel for the painting.

Is there any sort of mental therapy or spirituality to your work?

Part of the thing with horses, and with art, is that you can’t avoid a creator God idea – but a spiritual connection. There’s no way to do it without accepting that. I always try to avoid mentioning the issue of God, or belief in God. ‘Cause I feel like people have so much baggage with it. But that’s part of the spirituality that I was talking about – just not wanting to freak people out with “God talk”, because it’s part of the thing with horses, and with art, I think you can’t avoid a spiritual connection.

Share