Dark Art – Obrazrat

- Curation and interview by Diana M. Ahuixa

- Published:

- In Dark Art Feature

It appears that your masks incorporate organic materials. What is the significance of using these elements, and how do they contrast with the more structured, man-made nature of the mask form itself?

My works often include natural elements: branches, roots, pearls, horns, bones, stones, cotton. Recently, I started incorporating metal as well. I use these elements for two reasons. The first is to preserve what is already beautiful in its natural form and does not need imitation. Why invent a branch when it lies on the ground after a storm? The second is “giving a second life.” This applies to bones and horns found in attics and flea markets. I feel compassion for the lives taken for trophies, and I try to give them a new purpose. In the end, the natural elements undergo a metamorphosis, merging with my ideas.

Your art is a very consistent vision across different mediums. How do you see your identity as an artist reflected in the masks you create, and how do they serve as a personal form of expression for you?

I cannot fully see my own “artistic self” — an artist has no mirror for that. Only someone else can perceive it, and even then, subjectively: “beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

For me, the unity of art is not only in self-reflection (although that is important), but in the ability to be a conduit between something ephemeral and the viewer, and in the conscious choice of the themes I explore.

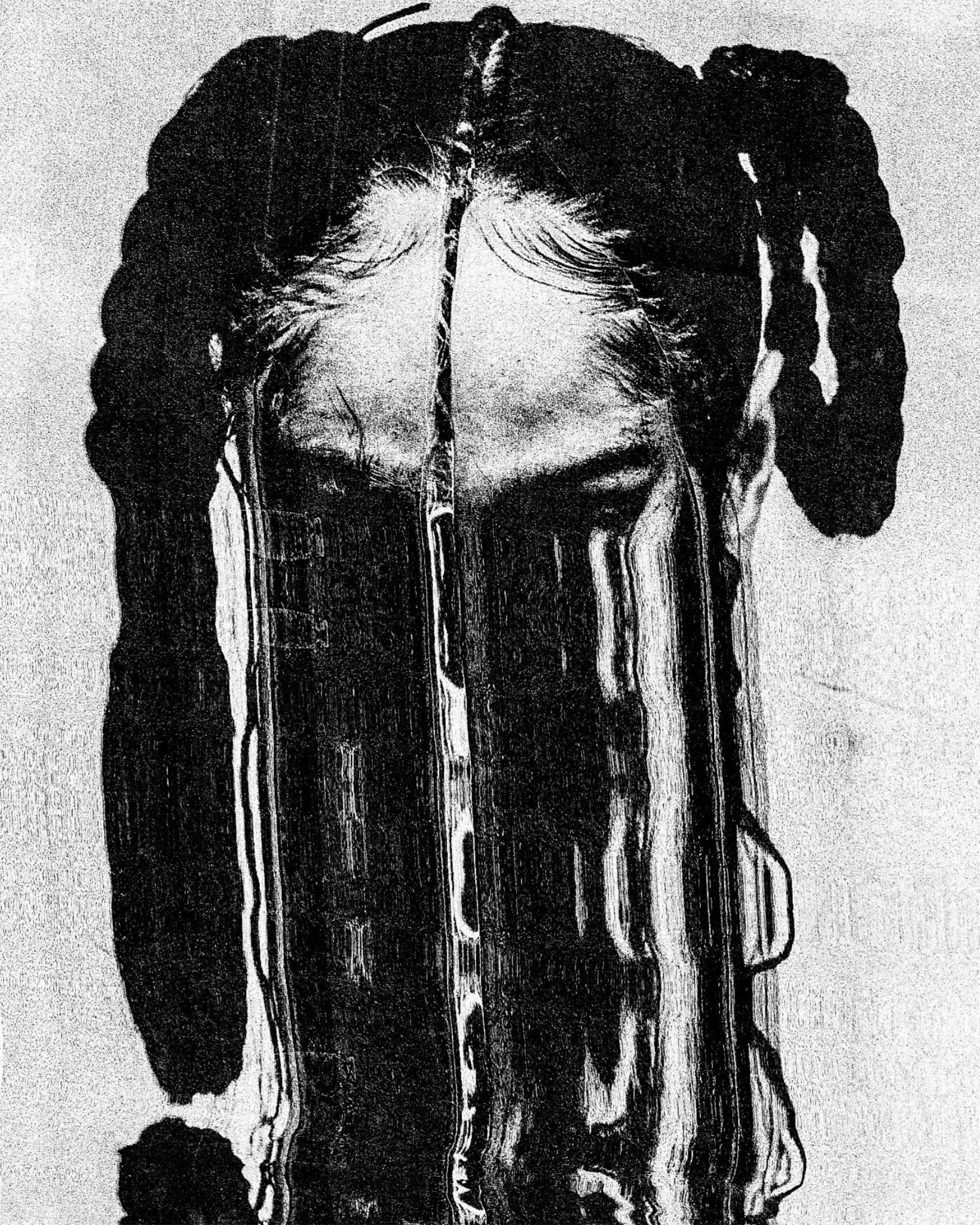

My self-expression is built around working with negative thoughts and experiences. I create a beautiful shell for them, where darkness and beauty coexist. This contrast attracts and unsettles at the same time. A mask may be full of sores, but if they are made of pearls, it draws attention and becomes the start of a conversation with the viewer.

What draws you to the mask as a medium? Is it the history of ritual and disguise, or does it serve a more personal, artistic purpose for you?

The mask as a medium came into my life by chance. I trained as a fashion designer, but I was creating images rather than clothes. I put too much meaning and detail into the clothing, and ended up choosing models not for the clothes, but to fit the concept. At some point, I made masks — new faces for the models. It looked striking, yet absurd, and I left the fashion industry.

Then came theater, circus, and film — everywhere I hid the person beneath an image, creating prosthetic makeup, SFX, and costumes that completely transformed identity. At first, it seemed like misanthropy, but over time I began to understand what I was doing.

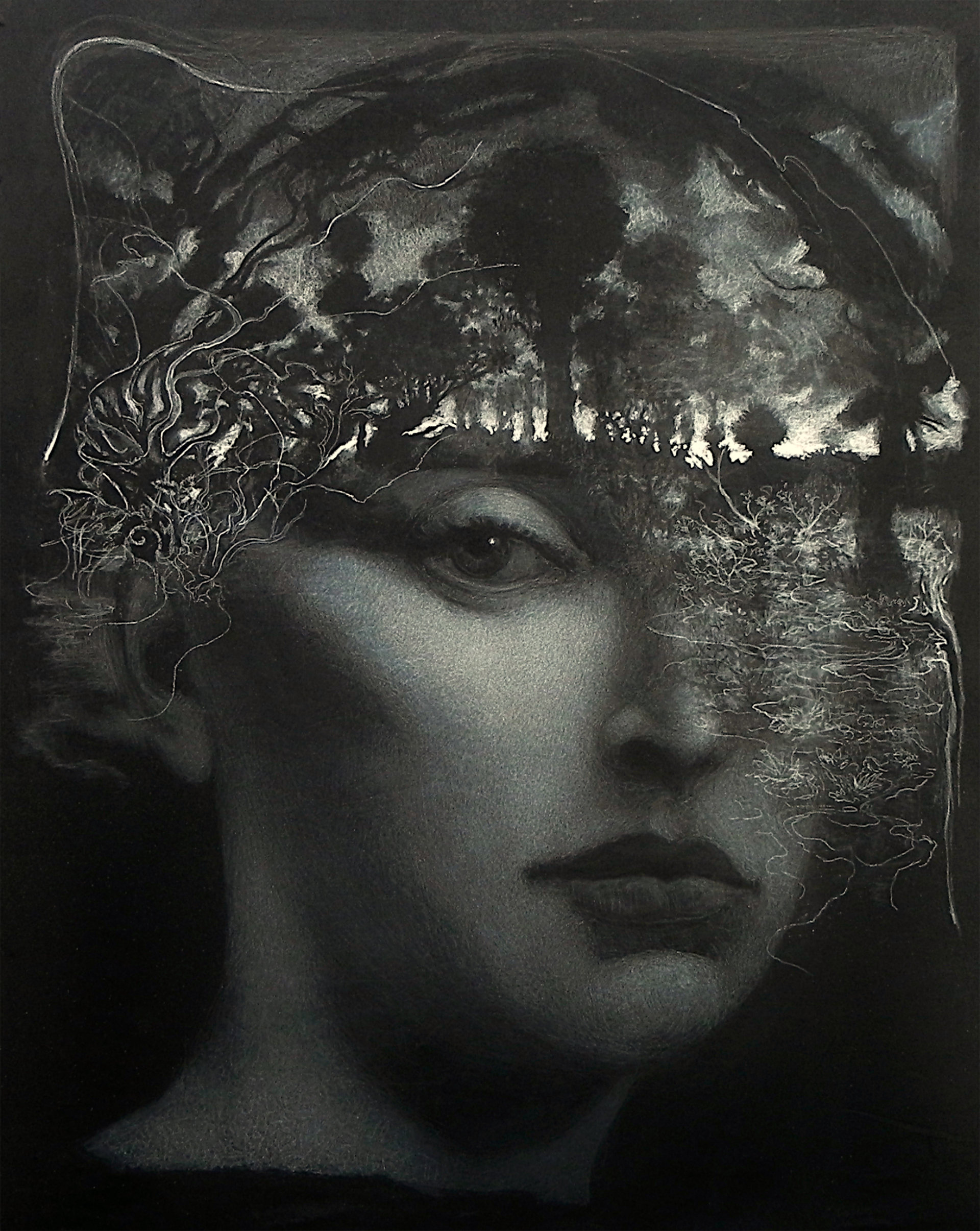

Gradually, I started creating my own characters and entire stories — a whole universe. But that work proved too heavy for me at the moment. I identified several areas that inspire me most: mythology (forest symbolism), psychology, and, oddly enough, people.

Through my art, I speak to people about their inner wounds using mythical imagery. The mask became my universal key to another soul: Without a face, the body loses meaning, and we always perceive another face as a conversational partner.

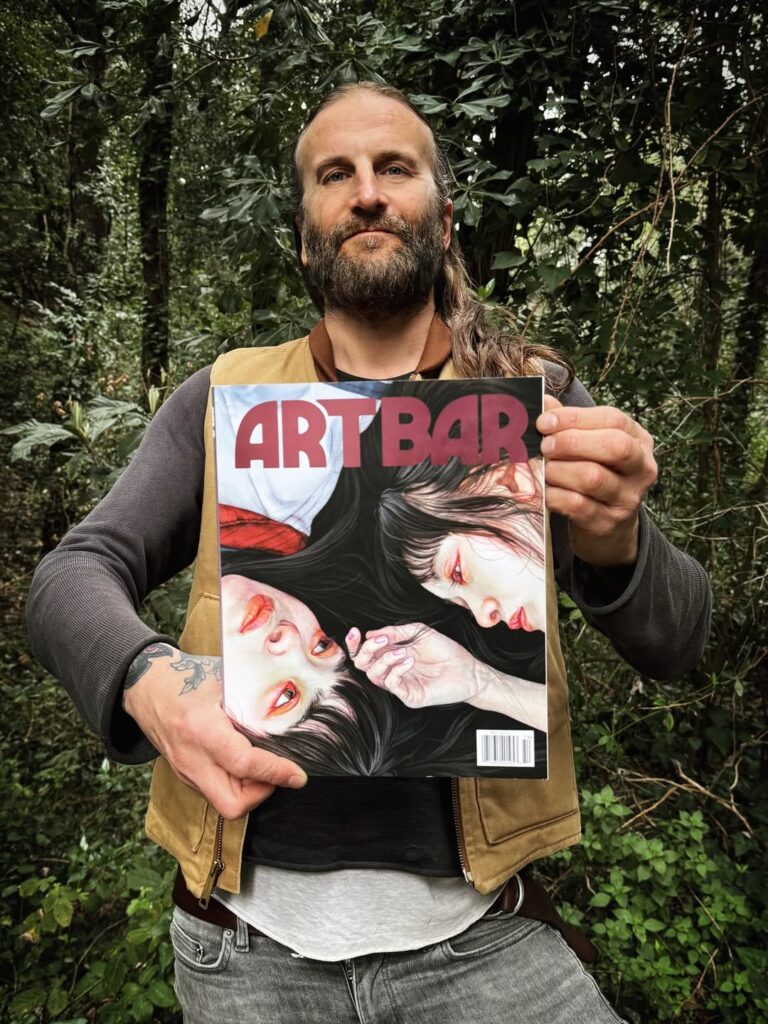

Since Mothmeister is being interviewed as well, how did your collaborations come about?

Mothmeister was one of my idols back in high school. Their art showed me that beauty is not limited to glossy magazines or museums. Several years ago, I nervously reached out and offered my masks. I did not expect a response, but we ended up creating several collaborative characters. Our worlds are different, yet the artistic atmospheres often intersect — which makes collaboration feel natural and harmonious.

The dark art genre sometimes exists outside of the mainstream art world. Has the intense and provocative nature of your work created any unique challenges for you in seeking gallery representation?

The dark art genre is rarely accepted in galleries, and my works hardly make it there. I compile catalogs, contact galleries, but mostly receive rejections. Exceptions include solo exhibitions and projects involving many artists, like those with Mothmeister or Fashion for Bank Robbers (by Carina Shoshtary). But this is not a tragedy: the internet allows me to find kindred spirits all over the world. Thanks to this, I can continue creating.

Share

You might also like ...

Dark Art – Ariel de la Vega

Your drawings are noted for their use of a white line on a black surface. What is the significance of this inversion of traditional drawing,

Dark Art – The Lijilja

Your work is deeply personal. How did this style of performance develop for you? Were there mentors who shaped it? How did your mode of

Dark Art – Sven Harambasic

In an interview, you mentioned that you prefer to deal with “isolated, inner worlds” rather than wider social commentary. How do you find and explore

Dark Art – Samuel Araya

The dark art genre sometimes exists outside of the mainstream art world. Has the intense and provocative nature of your work created any unique challenges