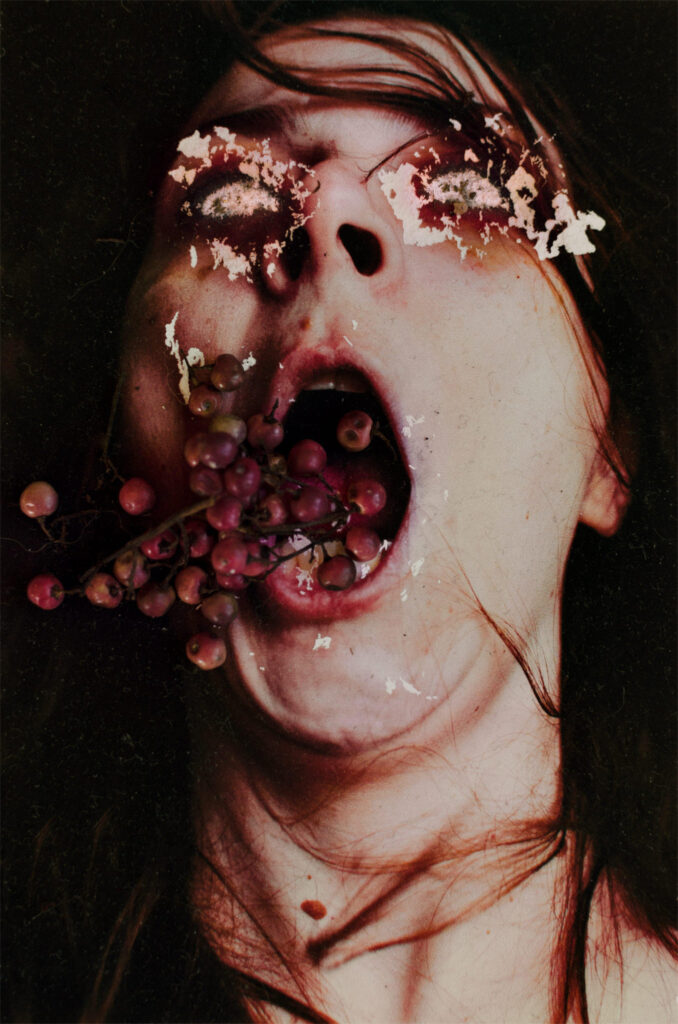

Dark Art – Melissa Giowanella

- Curation and interview by Diana M. Ahuixa

- Published:

- In Dark Art Feature

How did your background in theater influence your transition into fine art photography, especially your use of self-portraiture?

Art entered my life through theater. When I first stepped onto the stage, as a teenager, I discovered I was an artist. I’ve always been shy and introverted. But with theater, I felt authentic and free. Since then, there hasn’t been a day in my life when art wasn’t present.

Fine art photography entered my life by accident. I was already working in theater as an actress and a freelance artist; I did a bit of everything, including cinema and production projects. In 2012, I had the chance to study photography and I went into it out of curiosity and without any expectations. I knew nothing about photography and had never even held a professional camera in my life. During the course, I learned a little about a wide variety of photographic topics, that’s when I was introduced to fine art photography, a moment that changed my life. With self-portraits, I discovered I had the perfect tool — not only to train as an actress, but also to bring to life any idea that crossed my mind. With theater, I find my place in the world, but with photography, I learned to express my spirit. In fine art photography, I discovered that I could stage my own stories in a different way, with more autonomy and freedom of experimentation.

As a legacy of theater, my images have a very pronounced staging, with a lot of drama, both visually and conceptually.

As an artist, I don’t define myself as an actress or a photographer. For me, both careers are inseparable. I bring theater to photography and vice versa; they complement each other and enrich each other.

How does embracing the unexpected shape the final outcome of projects? What is the relationship between control and chance in this process?

The unexpected is an inevitable part of the creative process. I’m a very controlling person who enjoys in-depth processes with extensive study of both the conceptual and technical aspects. Photography taught me to let my control take over only in pre-production, because no matter how much I plan, the work will never turn out exactly as I initially conceived. And this doesn’t mean failure as an artist; quite the opposite. Planning provides a framework for you to begin your journey. The creative process demands that we remain open to the unexpected. This sensitivity and willingness to change course is what makes the final work stronger, more interesting, and more meaningful than any initial plan.

How does the art foster dialogue or change perceptions on a particular social issue, such as the representation of women? For me, art is a space for healing that starts within me. I talk about things that hurt and disturb me, and this comes from a very sensitive and genuine place; they are anxieties that I can’t suppress and that end up overflowing.

When you create with the intention of sharing, you find others who feel the same way, and this connection itself becomes a powerful tool for social transformation. Furthermore, art can connect with our emotions and create empathy. In my project “MATER”, I explore the way that a woman’s worth is still tied to her ability to have children. The project began from my anguish at being seen as worthless for choosing not to have children. And as I developed the project, sharing and holding exhibitions, a dialogue opened up with women who are mothers and who appropriated the works to express their painful experiences with motherhood. But what made me happier was receiving so many messages from men who said that seeing my work made them more aware of the issue and made them see injustices they hadn’t previously noticed. In a way, people with different experiences of motherhood came together to reflect on the topic, and I believe this is the first step toward promoting change in society.

As an artist, it’s very important for me that my work be a space for dialogue and reflection. When I create a work, I’m learning about the topic as much as the audience, and it’s not my place to provide answers or point out what’s right or wrong.

How is the right balance found between critical message and aesthetic composition in the work?

I don’t think there’s a recipe for what’s right; each artist has their own language, and the imbalance between critical message and aesthetic composition can even be part of that. But in my work, the concept is as important as the aesthetic composition — the two complement and strengthen each other. I believe artists need to be constantly developing, always studying, seeking to challenge themselves and improve with each work. A technically perfect image without a concept becomes something empty that doesn’t touch the audience. And a strong message in an unintentionally sloppy composition weakens the work.

But of course, art is an open field, and perfection and imperfection are highly subjective. I’m passionate about the baroque visual aspect, but my work is also heavily influenced by horror and dark art, which can generate images that are considered beautiful by some and repulsive by others. It’s impossible to please everyone, but I believe that every element of a work must be intentional, whether to enchant or to disturb.

What advice is given to aspiring artists who want to use their work to make a social critique?

I think the most important thing when creating something in the realm of social criticism is that it stems from genuine anguish. Even if you want to talk about something that isn’t a personal experience, it must be something that truly touches you. Nowadays, people love to create controversy, seek engagement, or do something because a certain topic is trendy. This is dangerous because it often dilutes our truth as artists and results in shallow and generic work. Each artist is unique in their vision, their sensitivity, and their way of expressing themselves. Audiences truly connect with emotions and truth, not with fleeting trends. In difficult times, your audience will be your support. It’s not an easy or quick path, but it’s important to protect your authenticity. It’s the only way for your work to be relevant and endure.

Another important point is to ensure you’re protected from all the hate that social criticism often receives. It’s important to separate your work from your personal essence so as not to become too vulnerable. I’ve heard horrible things about myself and my work, and if not for my conviction that my voice and the issues I address are important, I would have been deeply hurt. I believe in what I say, so I feel strong enough to fight for it. The world already hurts us enough. That’s why we should make art to heal, not to be hurt.

Share

You might also like ...

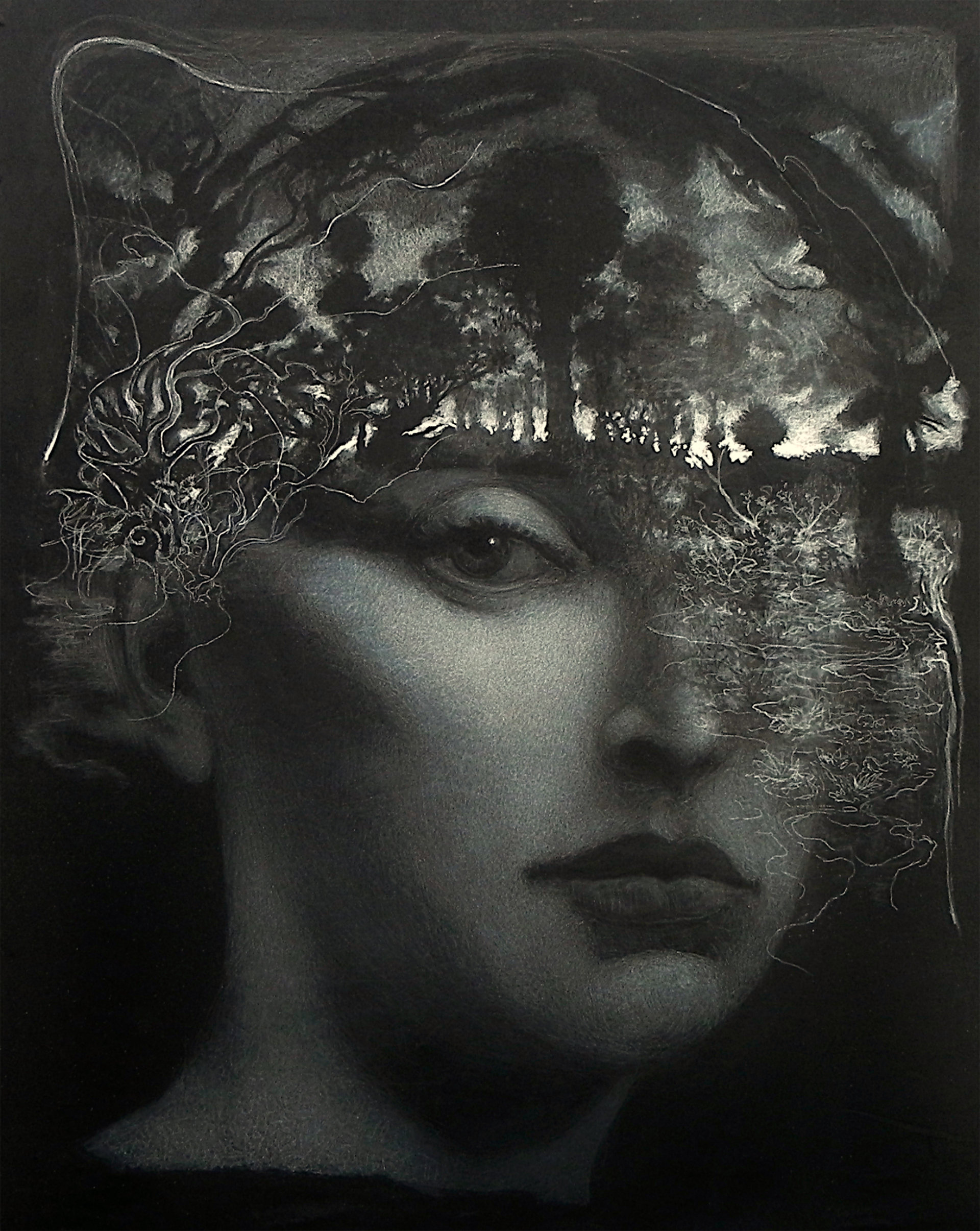

Dark Art – Ariel de la Vega

Your drawings are noted for their use of a white line on a black surface. What is the significance of this inversion of traditional drawing,

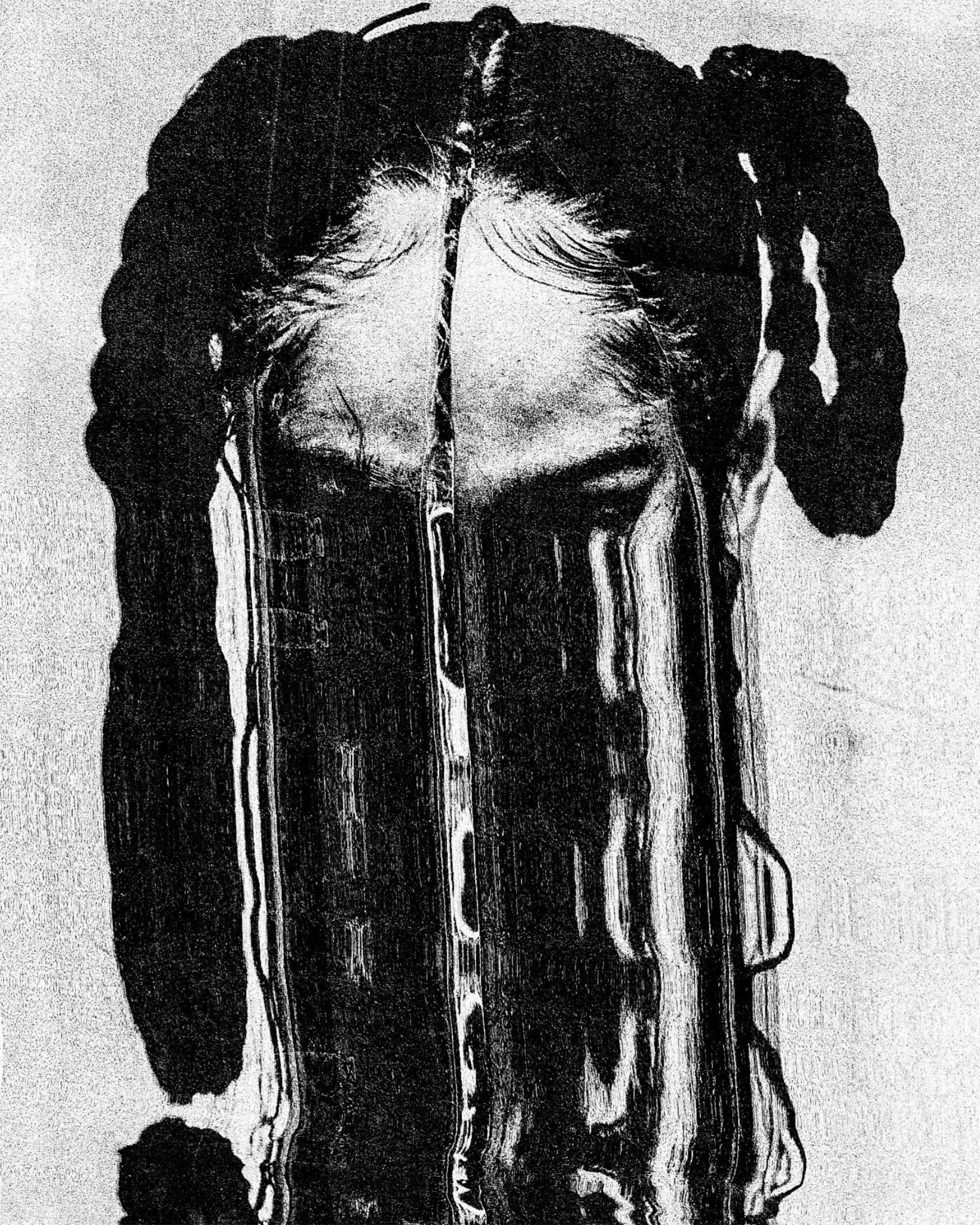

Dark Art – The Lijilja

Your work is deeply personal. How did this style of performance develop for you? Were there mentors who shaped it? How did your mode of

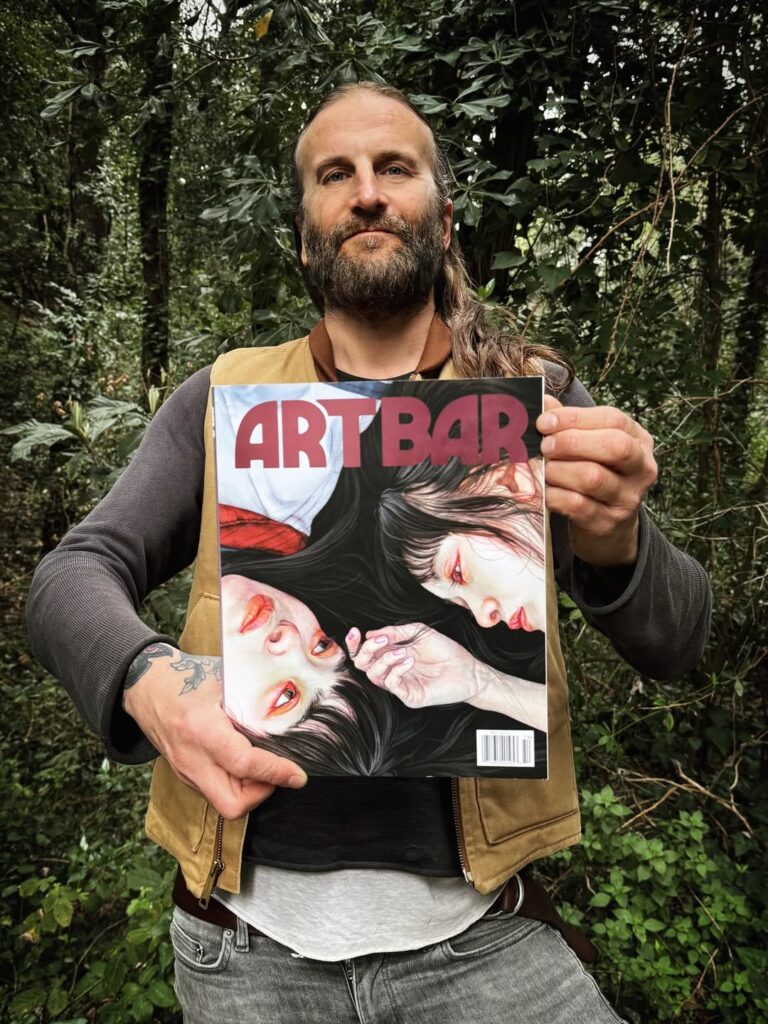

Dark Art – Sven Harambasic

In an interview, you mentioned that you prefer to deal with “isolated, inner worlds” rather than wider social commentary. How do you find and explore

Dark Art – Samuel Araya

The dark art genre sometimes exists outside of the mainstream art world. Has the intense and provocative nature of your work created any unique challenges