Various Artists: Shadow Work

- Story by KF Sydney.

- Curation and Interviews by Diana M. Ahuixa.

- Published:

- In Features

Healing the Jungian shadow-self through dark art.

Nightmare imagery has weaved its way through art for as long as humans have been dreaming. Hieronymous Bosch, Gustave Doré, and Francisco Goya have famously painted the horrifying demons of both the underworld and Hell on earth, in addition to Goya’s iconic depiction of nightmares in The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. These are just a few notable examples of the supernatural terrors lodged firmly within the heart of Western art history. Dark art has evolved through the ages but remains far outside the interest of mainstream art galleries and criticism.

This is in part because the current incarnation of dark art — and its normie twin, contemporary art — were separated at birth in the late 19th and early 20th century. This was largely a result of class. While modernist painters like Cézanne and Toulouse-Lautrec were creating a thirst among the canvas-collecting echelons of society for visual experimentation, writers like James Malcolm Rymer, Thomas Peckett, J.S. Le Fanu and Bram Stoker were stoking sensational mass-marketable tales of sex, horror, and gore for an increasingly-literate (and increasingly less-religious) public. These books needed illustrators — preferably ones who could render bizarre monsters and their blood-stained victims using every tool of vivid realism. By the 1930s, these stories were published in magazines with painted covers and starting to creep onto movie screens.

The path of art started to fork: Artists who wanted to gamble their careers on the bourgeois’ ability to appreciate their novel twist on realism went one way, and those banking on the taste of ordinary people went the other. If you painted a banana strangely you were a fine artist; if you painted a strange banana you were an illustrator. In both cases, audiences were seeing what they had never seen before. Although these paths have crisscrossed aesthetically too many times to count (such as in the haunted expressionistic wash basin of Francis Bacon and Joel-Peter Witkin’s sinister reanimation of Victorian photography), in commercial terms they’ve remained separate ever since.

This is beginning to change. Galleries devoted entirely to dark art began to pick up steam in the 1990s; born from the overflow of tattoo culture and the generation raised on pulp-horror imagery in ’70s and ’80s movies, comics, and books that were now all grown up and able to afford a painting or a framed print. The internet accelerated the process by a new proliferation of images and new millionaires able to afford them. Today, it’s possible to find dark artists who’ve never had to earn their crust shooting an album cover, designing a video game boss, or embellishing an edition of The Collected Edgar Allan Poe.

As the space for dark artists to be themselves and follow their own narratives expands, different aspects of creative “darkness” have emerged as central to the genre. Many artists describe using the traditional spiritual and pop-horror symbolism associated with the Gothic in a semi-ritualized way to access new psychological spaces.

Like the traditional dances and theatres of spiritual possession found in Africa, Afro-Caribbean nations, and the Pacific Islands, macabre artist duo Mothmeister describes donning a mask as a portal to an altered state:

Once the mask is on, the senses begin to vanish. You can’t see clearly. You can’t smell or hear. Breathing becomes shallow — ritualistic. The outside world fades. All that’s left is the being beneath the skin. You’re no longer pretending. You are the character. You’re locked in — fully immersed. Trapped in another self. And there’s a strange kind of freedom in that.

Artist Matt Mrowka describes entering such spaces as a creative necessity when conceiving his light-blasted nightmarescapes:

I usually have a loose daydream image or feeling I want to convey going into a piece but if the painting wants to take a different path, I tend to oblige. I’ve found if I let the process happen more like a channeling, then the work feels more honest and cathartic. Dark art can swing into the realm of “corny” or “cringe” very easily if it’s not completely honest.

Like the traditional dances and theatres of spiritual possession found in Africa, Afro-Caribbean nations, and the Pacific Islands, macabre artist duo Mothmeister describes donning a mask as a portal to an altered state:

Once the mask is on, the senses begin to vanish. You can’t see clearly. You can’t smell or hear. Breathing becomes shallow — ritualistic. The outside world fades. All that’s left is the being beneath the skin. You’re no longer pretending. You are the character. You’re locked in — fully immersed. Trapped in another self. And there’s a strange kind of freedom in that.

Artist Matt Mrowka describes entering such spaces as a creative necessity when conceiving his light-blasted nightmarescapes:

I usually have a loose daydream image or feeling I want to convey going into a piece but if the painting wants to take a different path, I tend to oblige. I’ve found if I let the process happen more like a channeling, then the work feels more honest and cathartic. Dark art can swing into the realm of “corny” or “cringe” very easily if it’s not completely honest.

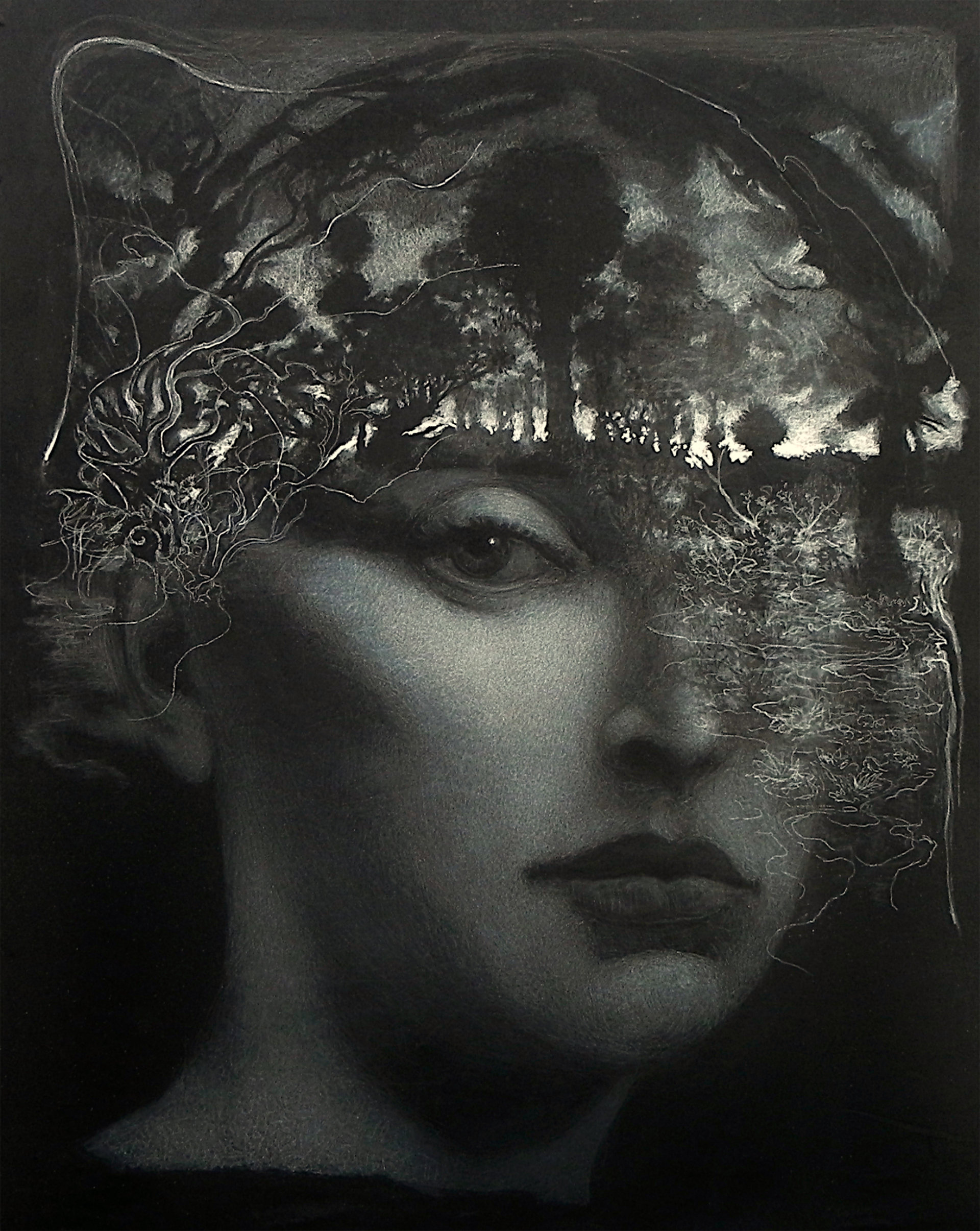

“I start from the dark to imagine a timeless dimension,” says illustrator Ariel De La Vega when asked why he prefers to draw on black surfaces. “A space where different planes coexist and the world of symbols and dreams live together. It’s where my psyche, like a mirror oriented towards the internal void, reveals its images…I am in no hurry and have no set goals; I enjoy the process.”

De La Vega alludes to a dark space all of us inhabit every day: the moment we close our eyes. To close our eyes is to enter a space where the outer world is less important than the inner one – a place of dreaming. The dark is inherently, experientially, indelibly linked to not just the danger and privacy of night, but to psychological spaces and the monsters of the unconscious.

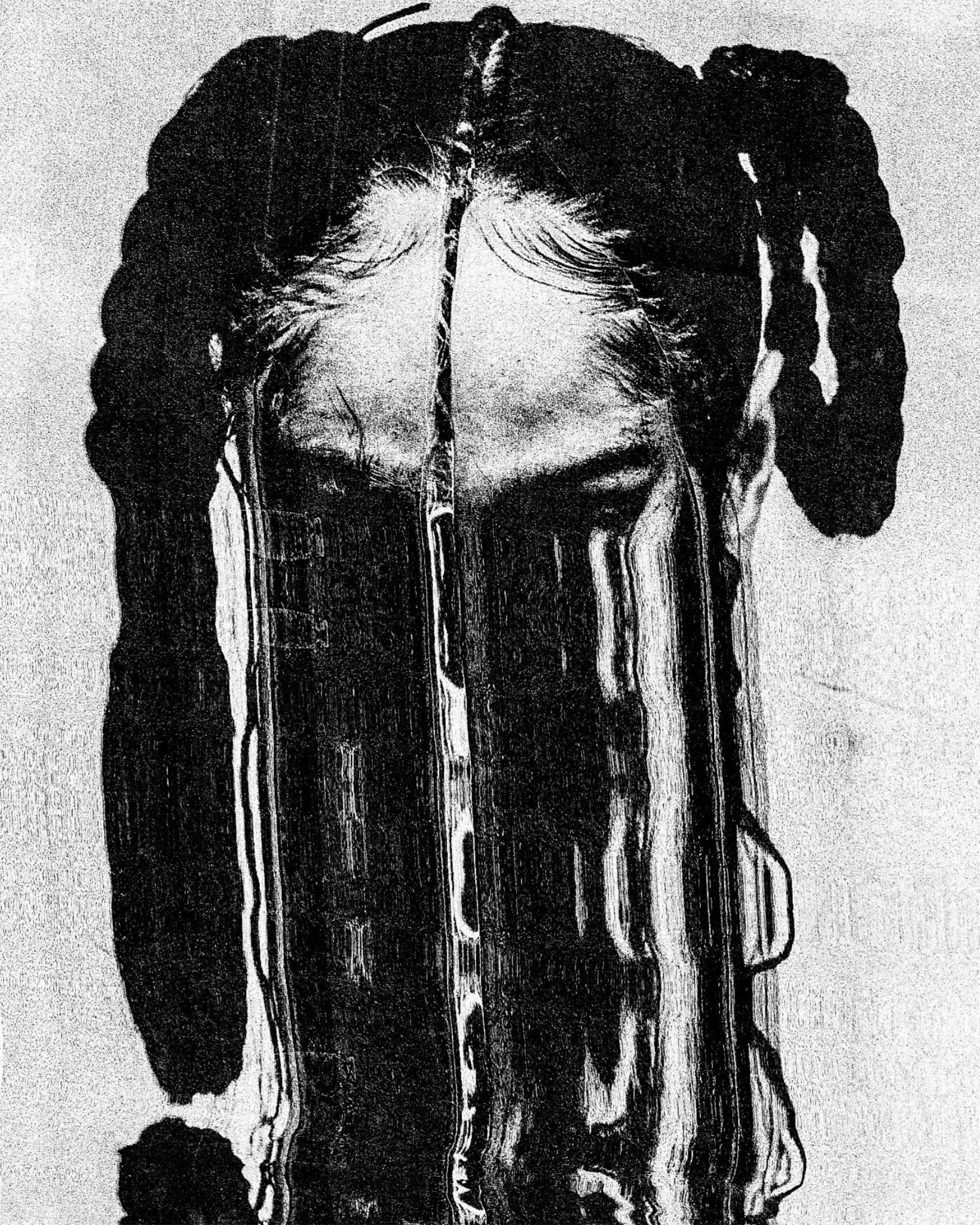

In his dramatic and enigmatic manipulations of traditional iconography, illustrator Django Nokes speaks to our inherent shadow-self:

It’s about creating curiosity: something unsettling that still draws you in. My philosophy is that true beauty often carries a shadow, and true horror often hides a strange kind of grace. I want my work to live right in that fragile space between the two.

It is no coincidence that spiritual imagery permeates dark art. As Carl Jung emphasized, faith and magic were often the pre-Enlightenment world’s most common way of dealing with distress and disorder. While the modern artist may understand that the right pill can help, creative practices that use ritual to acknowledge and give shape to personal suffering — making it visible to a community that can respond — still hold tremendous value. Mothmeister opines:

We’ve been atheists from the very beginning — and remain so without doubt. But atheism doesn’t mean indifference. Quite the opposite. Religion, to us, is one of the most fascinating human inventions — a theatre of belief, ritual, control, ecstasy, and fear. The concept of surrendering to a higher power, of building entire lives around unseen forces…it’s both beautiful and terrifying. It transcends the individual.

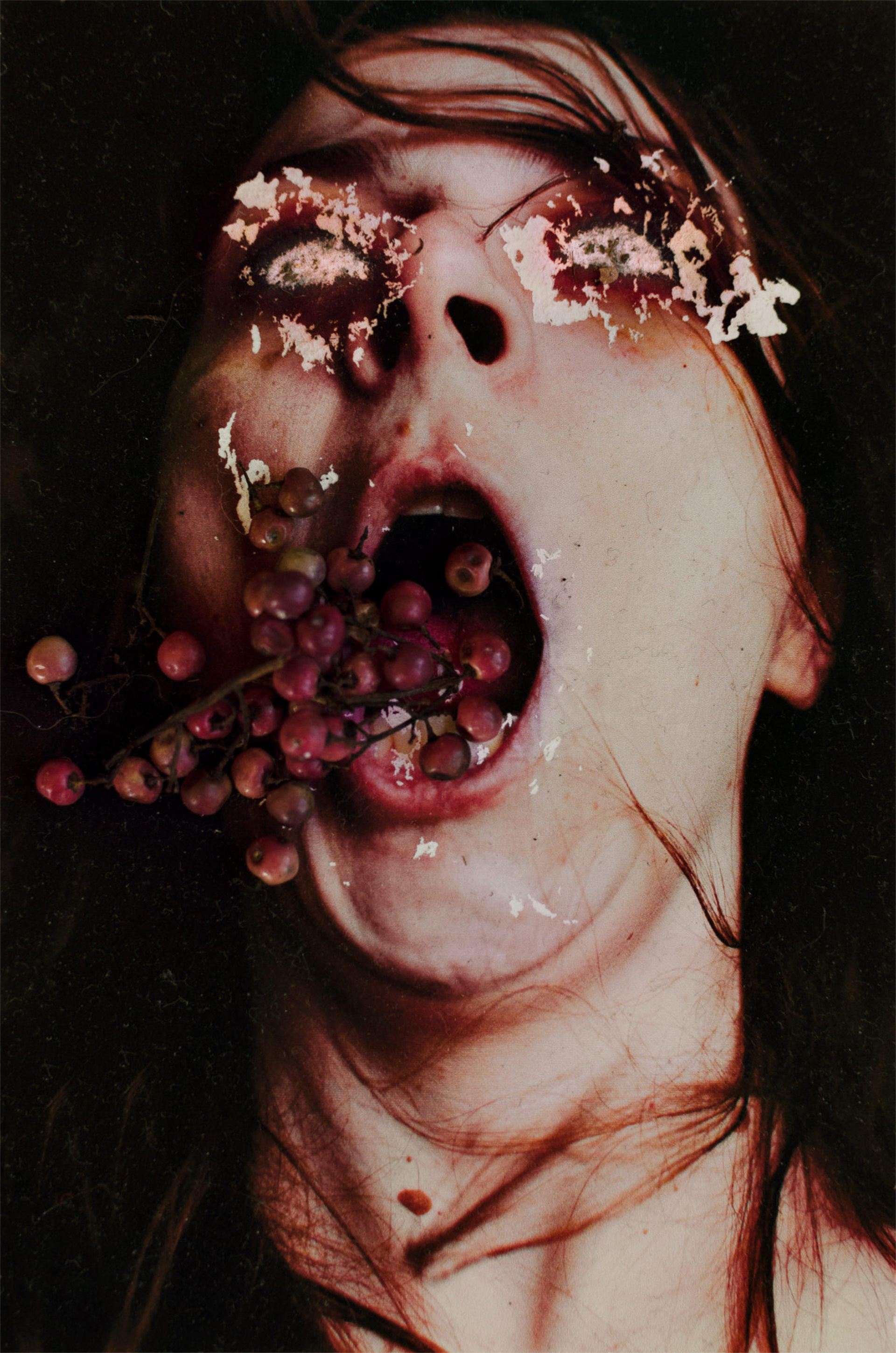

Sculptor Emil Melmoth describes the influence of traditional religious practices on his grotesquely ecstatic amalgamations of altarpiece statuary and medical moulage:

In Mexico, since our origins, we have had a very close relationship with death. In the pre-Hispanic period great importance was given to rituals, offerings and even sacrifices. There has always been a cult of death, from symbolic and ritual aspects to events full of blood and suffering, but at the same time of great admiration and recognition for what they represented.

Later came Catholicism where Christ is represented bloody, carrying his cross, hurt by his crown of thorns, scourged until he bleeds and dies. I have been struck by how the cult of death is manifested from our pre-Hispanic origins and later with the mixture of other religious traditions, mainly Catholicism because it is the largest religion in Latin America. Death is always impregnated with the crudest things such as suffering, blood, sacrifice, but also related to the beauty of the transcendence of the spirit.

Dark art’s historical precedent appears in 18th century Romanticism, often described as a spiritualizing and emotion-forward reaction against the technological innovations of the Enlightenment. It is quite fitting that now, at a time when every day we see into the bright light of technology the new ways that light is going to be used against us by those in power, artists are investigating the value of remaining in the shadows. No matter what progress we make, everyone has nightmares, everyone dies, and no one knows how to deal with it.

To the degree our technological overlords elude tragedy in their lives, they have often done it by exacerbating the tragedies in ours. In a world that’s devolved from clashes of ideology and tradition into a neo-feudal struggle between self-interested power brokers, the Jungian shadow-self hasn’t so much shrunk as gone public: Everyone now feels like an exposed nerve at the mercy of an indifferent and arbitrary state. It isn’t difficult to see why a thirst for the humanism of transforming private pain into public catharsis is becoming one of the few things people can agree on.

It is important to say that despite its introspective and occult tendencies, Romanticism did eventually achieve things in the public sphere — the European revolutions in the 19th century were heavily influenced by Romantic ideals of self-invention and Romantic poets were among the most ardent revolutionaries. Dark art may be just one aspect of a widening understanding of the deeper sources of our pain. The first step to illumination is to admit we are in the dark.

Scroll down to see the entire collection of artists curated by Diana M. Ahuixa.

Share